Overview of Amino Acid

This entry is from Wikipedia, the leading user-contributed encyclopedia.

For the structures and properties of the standard proteinogenic amino acids, see List of standard amino acids.

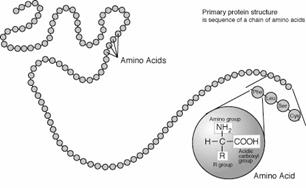

In chemistry, an amino acid is a molecule that contains both amine and carboxyl functional groups. In biochemistry, this term refers to alpha-amino acids with the general formula NH2CHRCOOH.[1] These are molecules where the amino and carboxylate groups are attached to the same carbon, which is called the α–carbon. The various alpha amino acids differ in which side chain (R group) is attached to their alpha carbon. This can vary in size from just a hydrogen atom in glycine, through a methyl group in alanine, to a large heterocyclic group in tryptophan.

Alpha-amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. Proteins form via the condensation of amino acids to form a chain of amino acid “residues” linked by peptide bonds. Each different protein has a unique sequence of amino acid residues; this sequence is the primary structure of the protein. Just as the letters of the alphabet can be combined to form an almost endless variety of words, amino acids can be linked in varying sequences to form a huge variety of proteins.

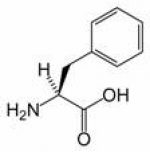

Phenylalanine is one of the standard amino acids.

There are twenty standard amino acids used by cells in protein biosynthesis, and these are specified by the general genetic code. These twenty amino acids are biosynthesized from other molecules, but organisms differ in which ones they can synthesize and which ones must be provided in their diet. The ones that cannot be synthesized by an organism are called essential amino acids.

Contents

1. Overview

1.1. Functions in proteins

1.2. Non-protein functions

2. General structure

2.1. Isomerism

3. Reactions

3.1. Peptide bond formation

3.2. Zwitterions

4. Hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids

5. Table of standard amino acid abbreviations and side chain properties

6. Nonstandard amino acids

7. Uses in technology

8. Nutritional importance

9. References and notes

10. Further reading

11. External links

1. Overview

Amino acids are the basic structural building units of proteins. They form short polymer chains called peptides or longer chains either called polypeptides or proteins. The process of such formation from an mRNA template is known as translation which is part of protein biosynthesis. Twenty amino acids are encoded by the standard genetic code and are called proteinogenic or standard amino acids. Other amino acids contained in proteins are usually formed by post-translational modification, which is modification after translation in protein synthesis. These modifications are often essential for the function or regulation of a protein; for example, the carboxylation of glutamate allows for better binding of calcium cations, and the hydroxylation of proline is critical for maintaining connective tissues and responding to oxygen starvation. Such modifications can also determine the localization of the protein, e.g., the addition of long hydrophobic groups can cause a protein to bind to a phospholipid membrane.

1.2. Non-protein functions

The twenty standard amino acids are either used to synthesize proteins and other biomolecules, or oxidized to urea and carbon dioxide as a source of energy.[2] The oxidation pathway starts with the removal of the amino group by a transaminase, the amino group is then fed into the urea cycle. The other product of transamidation is a keto acid that enters the citric acid cycle.[3] Glucogenic amino acids can also be converted into glucose, through gluconeogenesis.[4]

Hundreds of types of non-protein amino acids have been found in nature and they have multiple functions in living organisms. Microorganisms and plants can produce uncommon amino acids. In microbes, examples include 2-aminoisobutyric acid and lanthionine, which is a sulfide-bridged alanine dimer. Both these amino acids are both found in peptidic lantibiotics such as alamethicin.[5] While in plants, 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid is a small disubstituted cyclic amino acid that is a key intermediate in the production of the plant hormone ethylene.[6]

In humans, non-protein amino acids also have biologically-important roles. Glycine, gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate are neurotransmitters and many amino acids are used to synthesize other molecules, for example:

• Tryptophan is a precursor of the neurotransmitter serotonin

• Glycine is a precursor of porphyrins such as heme

• Arginine is a precursor of the hormone nitric oxide

• Carnitine is used in lipid transport within a cell,

• Ornithine and S-adenosylmethionine are precursors of polyamines,

• Homocysteine is an intermediate in S-adenosylmethionine recycling

Also present are hydroxyproline, hydroxylysine, and sarcosine. The thyroid hormones are also alpha-amino acids.

Some amino acids have even been detected in meteorites, especially in a type known as carbonaceous chondrites.[7] This observation has prompted the suggestion that life may have arrived on earth from an extraterrestrial source.

2. General structure

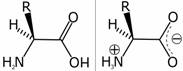

In the structure shown below, the R represents a side chain specific to each amino acid. The central carbon atom called Cα is a chiral central carbon atom (with the exception of glycine) to which the two termini and the R-group are attached. Amino acids are usually classified by the properties of the side chain into four groups. The side chain can make them behave like a weak acid, a weak base, a hydrophile if they are polar, and hydrophobe if they are nonpolar. The chemical structures of the 20 standard amino acids, along with their chemical properties, are cataloged in the list of standard amino acids.

The general structure of an α-amino acid molecule,

with the amino group on the left and the carboxyl group on the right.

The phrase “branched-chain amino acids” or BCAA is sometimes used to refer to the amino acids having aliphatic side-chains that are non-linear; these are leucine, isoleucine and valine. Proline is the only proteinogenic amino acid whose side group links to the α-amino group, and thus is also the only proteinogenic amino acid containing a secondary amine at this position. Proline has sometimes been termed an imino acid, but this is not correct in the current nomenclature.[8]

2.1. Isomerism

Most amino acids can exist in either of two optical isomers, called D and L. The L-amino acids represent the vast majority of amino acids found in proteins. D-amino acids are found in some proteins produced by exotic sea-dwelling organisms, such as cone snails.[9] They are also abundant components of the peptidoglycan cell walls of bacteria.[10]

The L and D conventions for amino acid configuration do not refer to the optical activity, but rather to the optical activity of the isomer of glyceraldehyde having the same stereochemistry as the amino acid. S-Glyceraldehyde is levorotary, and R-glyceraldehyde is dexterorotary, and so S-amino acids are called L- even if they are not levorotary, and R-amino acids are likewise called D- even if they are not dexterorotary.

There are two exceptions to these general rules of amino acid isomerism. Firstly, glycine, where R = H, no isomerism is possible because the alpha-carbon bears two identical groups (hydrogen). Secondly, in cysteine, the L = S and D = R assignment is reversed to L = R and D = S. Cysteine is structured similarly (with respect to glyceraldehyde) to the other amino acids but the sulfur atom alters the interpretation of the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog priority rule.

3. Reactions

As amino acids have both a primary amine group and a primary carboxyl group, these chemicals can undergo most of the reactions associated with these functional groups. These include nucleophilic addition, amide bond formation and imine formation for the amine group and esterification, amide bond formation and decarboxylation for the carboxylic acid group. The multiple side chains of amino acids can also undergo chemical reactions. The types of these reactions are determined by the groups on these side chains and are discussed in the articles dealing with each specific type of amino acid.

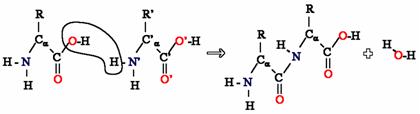

3.1. Peptide bond formation

As both the amine and carboxylic acid groups of amino acids can react to form amide bonds, one amino acid molecule can react with another and become joined through an amide linkage. This polymerization of amino acids is what creates proteins. This condensation reaction yields the newly formed peptide bond and a molecule of water. In cells, this reaction does not occur directly, instead the amino acid is activated by attachment to a transfer RNA molecule through an ester bond. This aminoacyl-tRNA is produced in an ATP-dependent reaction carried out by an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase.[11] This aminoacyl-tRNA is then a substrate for the ribosome, which catalyzes the attack of the amino group of the elongating protein chain on the ester bond.[12] As a result of this mechanism, all proteins are synthesized starting at their N-terminus and moving towards their C-terminus.

The condensation of two amino acids to form a peptide bond.

However, not all peptide bonds are formed in this way. In a few cases peptides are synthesized by specific enzymes. For example, the tripeptide glutathione is an essential part of the defenses of cells against oxidative stress. This peptide is synthesized in two steps from free amino acids.[13] In the first step gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase condenses cysteine and glutamic acid through a peptide bond formed between the side-chain carboxyl of the glutamate (the gamma carbon of this side chain) and the amino group of the cysteine. This dipeptide is then condensed with glycine by glutathione synthetase to form glutathione.[14]

In chemistry, peptides are synthesized by a variety of reactions. One of the most used in solid-phase peptide synthesis, which uses the aromatic oxime derivatives of amino acids as activated units. These are added in sequence onto the growing peptide chain, which is attached to a solid resin support.[15]

3.2. Zwitterions

As amino acids have both the active groups of an amine and a carboxylic acid they can be considered both acid and base (though their natural pH is usually influenced by the R group). At a certain pH known as the isoelectric point, the amine group gains a positive charge (is protonated) and the acid group a negative charge (is deprotonated). The exact value is specific to each different amino acid. This ion is known as a zwitterion. A zwitterion can be extracted from the solution as a white crystalline structure with a very high melting point, due to its dipolar nature. Near-neutral physiological pH allows most free amino acids to exist as zwitterions.

4. Hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids

Depending on the polarity of the side chain, amino acids vary in their hydrophilic or hydrophobic character. These properties are important in protein structure and protein-protein interactions. The importance of the physical properties of the side chains comes from the influence this has on the amino acid residues’ interactions with other structures, both within a single protein and between proteins. The distribution of hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids determines the tertiary structure of the protein, and their physical location on the outside structure of the proteins influences their quaternary structure. For example, soluble proteins have surfaces rich with polar amino acids like serine and threonine, while integral membrane proteins tend to have outer ring of hydrophobic amino acids that anchors them into the lipid bilayer, and proteins anchored to the membrane have a hydrophobic end that locks into the membrane. Similarly, proteins that have to bind to positively-charged molecules have surfaces rich with negatively charged amino acids like glutamate and aspartate, while proteins binding to negatively-charged molecules have surfaces rich with positively charged chains like lysine and arginine. Recently a new scale of hydrophobicity based on the free energy of hydrophobic association has been proposed [16].

Hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions of the proteins do not have to rely only on the side chains of amino acids themselves. By various posttranslational modifications other chains can be attached to the proteins, forming hydrophobic lipoproteins or hydrophilic glycoproteins.

5. Table of standard amino acid abbreviations and side chain properties

|

Amino Acid |

3-Letter |

1-Letter |

Side chain polarity |

Side chain acidity or basicity |

Hydropathy index [17] |

|

Alanine |

Ala |

A |

nonpolar |

neutral |

1.8 |

|

Arginine |

Arg |

R |

polar |

strongly basic |

-4.5 |

|

Asparagine |

Asn |

N |

polar |

neutral |

-3.5 |

|

Aspartic acid |

Asp |

D |

polar |

acidic |

-3.5 |

|

Cysteine |

Cys |

C |

polar |

neutral |

2.5 |

|

Glutamic acid |

Glu |

E |

polar |

acidic |

-3.5 |

|

Glutamine |

Gln |

Q |

polar |

neutral |

-3.5 |

|

Glycine |

Gly |

G |

nonpolar |

neutral |

-0.4 |

|

Histidine |

His |

H |

polar |

weakly basic |

-3.2 |

|

Isoleucine |

Ile |

I |

nonpolar |

neutral |

4.5 |

|

Leucine |

Leu |

L |

nonpolar |

neutral |

3.8 |

|

Lysine |

Lys |

K |

polar |

basic |

-3.9 |

|

Methionine |

Met |

M |

nonpolar |

neutral |

1.9 |

|

Phenylalanine |

Phe |

F |

nonpolar |

neutral |

2.8 |

|

Proline |

Pro |

P |

nonpolar |

neutral |

|

|

Serine |

Ser |

S |

polar |

neutral |

-0.8 |

|

Threonine |

Thr |

T |

polar |

neutral |

-0.7 |

|

Tryptophan |

Trp |

W |

nonpolar |

neutral |

-0.9 |

|

Tyrosine |

Tyr |

Y |

polar |

neutral |

-1.3 |

|

Valine |

Val |

V |

nonpolar |

neutral |

4.2 |

In addition to the normal amino acid codes, placeholders were used historically in cases where chemical or crystallographic analysis of a peptide or protein could not completely establish the identity of a certain residue in a structure. The ones they could not resolve between are these pairs of amino-acids:

|

Ambiguous Amino Acids |

3-Letter |

1-Letter |

|

Asparagine or aspartic acid |

Asx |

B |

|

Glutamine or glutamic acid |

Glx |

Z |

|

Leucine or Isoleucine |

Xle |

J |

|

Unspecified or unknown amino acid |

Xaa |

X |

Unk is sometimes used instead of Xaa, but is less standard.

6. Nonstandard amino acids

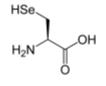

Aside from the twenty standard amino acids and the two special amino acids, there are a vast number of “nonstandard amino acids”. Two of these can be encoded in the genetic code, but are rather rare in proteins. Selenocysteine is incorporated into some proteins at a UGA codon, which is normally a stop codon.[18] Pyrrolysine is used by some methanogenic bacteria in enzymes that they use to produce methane. It is coded for with the codon UAG.[19]

The amino acid selenocysteine.

Examples of nonstandard amino acids that are not found in proteins include lanthionine, 2-aminoisobutyric acid, dehydroalanine and the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid. Nonstandard amino acids often occur as intermediates in the metabolic pathways for standard amino acids – for example ornithine and citrulline occur in the urea cycle, part of amino acid catabolism.[20]

Nonstandard amino acids are usually formed through modifications to standard amino acids. For example, homocysteine is formed by the transsulfuration pathway from cysteine or as an intermediate in S-adenosyl methionine metabolism,[21] while dopamine is synthesized from tyrosine, and hydroxyproline is made by a posttranslational modification of proline.[22]

7. Uses in technology

|

Amino acid derivative |

Use in industry |

|

Aspartame (aspartyl-phenylalanine-1-methyl ester) |

Low-calorie artificial sweetener |

|

5-HTP (5-hydroxytryptophan) |

Treatment for depression and the neurological problems of phenylketonuria. |

|

L-DOPA (L-dihydroxyphenylalanine) |

Treatment for Parkinsonism. |

|

Monosodium glutamate |

Food additive that enhances flavor. Confers the taste umami. |

8. Nutritional importance

Of the 20 standard proteinogenic amino acids, 10 are called essential amino acids because the human body cannot synthesize them from other compounds through chemical reactions, and they therefore must be obtained from food. Cysteine, tyrosine, histidine and arginine are considered as semiessential amino acids in children, because the metabolic pathways that synthesize these amino acids are not fully developed.[23]

|

Essential |

Nonessential |

|

Isoleucine |

Alanine |

|

Leucine |

Asparagine |

|

Lysine |

Aspartate |

|

Methionine |

Cysteine |

|

Phenylalanine |

Glutamate |

|

Threonine |

Glutamine |

|

Tryptophan |

Glycine |

|

Valine |

Proline |

|

Arginine* |

Serine |

|

Histidine* |

Tyrosine |

(*) Essential only in certain cases

Several common mnemonics have evolved for remembering the essential amino acids. PVT TIM HALL (“Private Tim Hall”) uses the first letter of each essential amino acid, including arginine.[24] Another mnemonic that frequently occurs in student practice materials is “These ten valuable amino acids have long preserved life in man”.[25]

9. References and notes

1. Proline is an exception to this general formula. It lacks the NH2 group because of the cyclization of the side chain.

2. Sakami W, Harrington H. “Amino acid metabolism”. Annu Rev Biochem 32: 355-98.

3. Brosnan J (2000). “Glutamate, at the interface between amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism”. J Nutr 130 (4S Suppl): 988S-90S.

4. Young V, Ajami A (2001). “Glutamine: the emperor or his clothes?” J Nutr 131 (9 Suppl): 2449S-59S; discussion 2486S-7S.

5. Whitmore L, Wallace B (2004). “Analysis of peptaibol sequence composition: implications for in vivo synthesis and channel formation.” Eur Biophys J 33 (3): 233-7.

6. Alexander L, Grierson D (2002). “Ethylene biosynthesis and action in tomato: a model for climacteric fruit ripening”. J Exp Bot 53 (377): 2039-55.

7. Llorca J (2004). “Organic matter in meteorites.” Int Microbiol 7 (4): 239-48.

8. Claude Liebecq (Ed) Biochemical Nomenclature and Related Documents, 2nd edition, Portland Press, 1992, pages 39-69 ISBN 978-1855780057

9. Pisarewicz K, Mora D, Pflueger F, Fields G, Marí F (2005). “Polypeptide chains containing D-gamma-hydroxyvaline.”. J Am Chem Soc 127 (17): 6207-15.

10. Van Heijenoort J (2001). “Formation of the glycan chains in the synthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan.”. Glycobiology 11 (3): 25R-36R.

11. Ibba M, Söll D (2001). “The renaissance of aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis”. EMBO Rep 2 (5): 382-7.

12. Lengyel P, Söll D (1969). “Mechanism of protein biosynthesis”. Bacteriol Rev 33 (2): 264-301.

13. Wu G, Fang Y, Yang S, Lupton J, Turner N (2004). “Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health”. J Nutr 134 (3): 489-92.

14. Meister A (1988). “Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification”. J Biol Chem 263 (33): 17205–8.

15. Carpino, L. A. (1992) 1-Hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole. An efficient Peptide Coupling Additive. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 4397-4398.

16. Urry, D. W. (2004). “The change in Gibbs free energy for hydrophobic association – Derivation and evaluation by means of inverse temperature transitions”. Chemical Physics Letters 399 (1-3): 177-183.

17. Kyte J & RF Doolittle (1982). “A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein”. J. Mol. Biol. (157): 105-132.

18. Driscoll D, Copeland P. “Mechanism and regulation of selenoprotein synthesis.”. Annu Rev Nutr 23: 17-40.

19. Krzycki J (2005). “The direct genetic encoding of pyrrolysine.”. Curr Opin Microbiol 8 (6): 706-12.

20. Curis E, Nicolis I, Moinard C, Osowska S, Zerrouk N, Bénazeth S, Cynober L (2005). “Almost all about citrulline in mammals”. Amino Acids 29 (3): 177-205.

21. Brosnan J, Brosnan M (2006). “The sulfur-containing amino acids: an overview”. J Nutr 136 (6 Suppl): 1636S-1640S.

22. Kivirikko K, Pihlajaniemi T. “Collagen hydroxylases and the protein disulfide isomerase subunit of prolyl 4-hydroxylases”. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol 72: 325-98.

23. Imura K, Okada A (1998). “Amino acid metabolism in pediatric patients”. Nutrition 14 (1): 143-8.

24. Distance Medical Biochemistry course from the University of New England.

http://www.faculty.une.edu/com/courses/bionut/distbio/obj-512/Chap39-pvttimhall.htm Access date 25 February 2006

25. Memory aids for medical biochemistry. http://mednote.co.kr/Yellownote/BIOCHMNEMON.htm Access date 25 February 2006

10. Further reading

• Doolittle, R.F. (1989) Redundancies in protein sequences. In Predictions of Protein Structure and the Principles of Protein Conformation (Fasman, G.D. ed) Plenum Press, New York, pp. 599-623

• David L. Nelson and Michael M. Cox, Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 3rd edition, 2000, Worth Publishers, ISBN 1-57259-153-6

11. External links

• Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry and The International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN)

• Molecular Expressions: The Amino Acid Collection

– Has detailed information and microscopy photographs of each amino acid.

• 22nd amino acid – Press release from Ohio State claiming discovery of a 22nd amino acid

• Amino acid properties – Properties of the amino acids (a tool aimed mostly at molecular geneticists trying to understand the meaning of mutations)

• Synthesis of Amino Acids and Derivatives

• Right-handed amino acids were left behind

• Amino acid solutions pH, titration curves and distribution diagrams – freeware